With just one day to go before the Paris 2024 opening ceremony, I have just come up with a new Olympic Event. I know - my timing sucks.

It’s a combination of the 4x100m relay, and the long jump. Stay with me...

Imagine the scene – the runner, baton-in-hand nears the end of the 400m lap, but rather than passing it on, she continues sprinting - as far as the long jump landing pit, throws herself into the sand and buries the baton, hurriedly raking over the sand afterwards. Once the sandpit judge is satisfied that it is thoroughly hidden, they raise a green flag. Next runner is free to go! She rushes to the long jump pit and launches into a frenetic search to find the baton, before running back to the track, completing a lap, and returning to the sand to bury the baton – and on we go.

What do you think? Could it catch on?

Strange then, how this kind of reflects the default approach to how we share and transfer knowledge. Carefully concealed in a SharePoint sandpit – when perhaps a more personal, relational approach would have been better and just more natural? A Peer Assist or ‘baton-passing’ approach for project handover might be a more effective action.

In a real-life baton pass, think about the careful and deliberate matching of pace, the hand stretching backwards requesting the baton, the holder carefully placing it in the receiver’s hand - have they got it now? – have they *really* got it? - a critical split-second when both are holding the baton simultaneously - and they're off. Now the giver can slow down knowing that nothing was dropped in the process.

Now of course sometimes, the next member of the knowledge relay team isn’t on the track yet – so putting the baton somewhere safe, discoverable and easy to grasp is the best we can do... But let’s try not to rush too quickly to the sandpit though – knowledge management is a team sport after all.

And nobody really likes getting sand in their shoes.

Seeing the whole elephant...

Used with permission from the family of Artist Robert Edward Weaver

It shouldn't surprise me after all this time, but it does.

I've conducted around 30 interviews in two different organisations in the last couple of months, as part of some KM strategy work. The answers to the question: "what does knowledge management mean to you?" are often so varied, and usually include just one or two components or approaches . People have such different perspectives on what knowledge management is - and it's rare for anyone to connect the different components together in any kind of holistic framework. "It's about how we get the right knowledge to the right person at the right time. Oh and it's to do with networks and conversations too."

To be fair, knowledge management has been poorly defined and communicated in the external world, so it's little wonder that people in organisations often approach it like the blind men and the elephant - each sensing a part, but not the whole, and drawing their own conclusions.

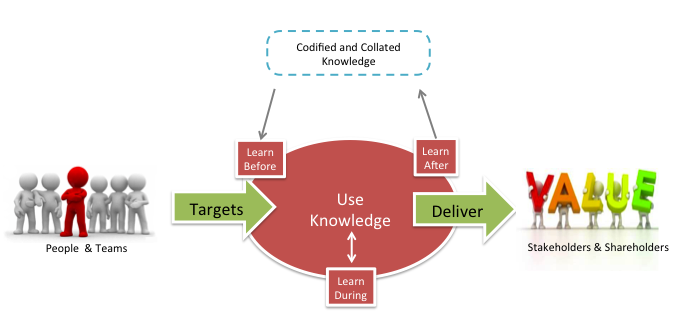

Here's a holistic model for knowledge management. It isn't new (it's based on the model from BP in Learning to Fly)- but it's still relevant and current today and does a good job of plotting a route through the KM landscape. Let me build it up for you.

Start with the day-to-day matter of performance management and project management, where people and teams agree to goals and targets in order to deliver value which generally takes the form of profits for shareholders - or value for stakeholders.

How do they do this? By using and developing knowledge - their own expertise, knowledge from the team, elsewhere in the organisation, from professional advisors or others outside the organisation.

It's a given that KM needs to connect directly to the goals and objectives of the organisation. So how does knowledge management improve, or accelerate the way in which they are achieved?

Firstly, through the application of learning. Learning before, during and after activities.

Without learning, we end up recycling old knowledge and documents - trapped between "connect and collect", but not creating anything new.

Learning before: how do we know that we've tapped into what the organisation already knows, and can we make sense of what it is knowing today?

Learning after: how good are we at really learning and applying lessons from stories of personal experience?

Learning during: do we have a culture of continuous learning, reviewing and improving?

With processes for learning before and after in place, it's important to manage the outputs of those processes - and to continue to refine, collate and curate a living, evolving, media-rich "knowledge bank", from which withdrawals and deposits can be made.

...but of course, the capture knowledge is just a shadow of the knowledge which will always remain in the heads of individual experts, and within networks of people with questions, answers, experience and ideas. The reserves in this human knowledge bank are far greater.

These networks and experts play a vital role in collating and curating knowledge on behalf of the organisation. They have the current awareness and they understand the most pressing business issues. Who better to steward the knowledge than an emergent community of subject matter experts and practitioners?

So now we've connected performance and project management with learning, learning with codification, and codification with networks, experience and expertise. The final part of the model recognises the role that culture and leadership behaviours and actions play to sustain an environment where these processes can thrive and interconnect.

What motivates people to make the time to learn, connect and collate knowledge such that the value and efficiencies have a chance to flow through and create the stories to inspire others? How can leaders reinforce and role-model this?

It can take a little time to give birth to this kind of a supportive culture - but then again, elephants to have the longest gestation period of any mammal, so we shouldn't be surprised.

Borrowing with pride, acknowledging with style, sharing with humility.

I was participating in a Twitter chat yesterday with staff from across the UK’s National Health Service, on the topic of quality improvement, facilitated by Hugh McCaughey, the NHS’s National Director of Improvement

One of the threads of discussion picked up on the opportunities for knowledge reuse, and Hugh used the phrase ‘Borrow with Pride’.

We’re all familiar with the idea of ‘Steal with Pride’ – (or ‘pinch with pride’, as Caroline, one of the other participants put it), but there is something in the idea of stealing and pinching which runs counter to the idea of a knowledge marketplace or a reciprocative - or even altruistic - knowledge-sharing environment.

Borrowing suggests that ownership remains unchanged, and the item will be treated with respect and care. Stealing….. well, you can join the dots on that one!

Acknowledgement is key to this – we should take pride not just in the fact that we discovered something of value, but in who we have borrowed from. We should wear the @ tags of recognition of those who have gone before us – those from whom we are learning - as medals of honour!

adapted from an image on www.sanantoniomag.com

(“Lacknowledgment” is one of my revised seven deadly syndromes of knowledge sharing - thanks Lynnette for the reminder!)

Most of the time we are borrowing insights, experiences, ideas – sometimes embodied in documents – but often not. So how do we make it easier for people to ‘borrow’ what we know (with confidence that they will acknowledge us, of course)?

I believe that most people are most likely to re-use something shared in the spirit of "I tried this and it worked for me" (good practice in my context) – “this was what we did”, “this was what we adapted from others”, “this was probably where we got lucky”… (thank you Google Inc for that last one). That kind of muted trumpeting requires the sharer to dial back on the PowerPoint gloss a little, be authentic and reduce the barriers to acceptance - to share with a little humility.

Perhaps that's what knowledge leadership is all about?

Image by Jessica Boyle

I'll get by with a little help from my friends

Two days ago I turned 50. There. I said it out loud!

One of the features of ‘milestone birthdays’ is that you receive a lot of empathy from your peers. This was demonstrated very practically at our ‘We’re all 50 this year’ school reunion in Devon, where I spent my childhood. (I'm in the back row, 8th in from the left).

Dawlish Comprehensive School - Class of 1984

It was lovely to see around 70 schoolmates with whom I’d long since lost touch, all together again thanks largely to the magic of Facebook events and some additional detective work by the organising committee.

What really struck me was the way in which we reconstructed our memories from 34 years ago by combining fragments. None of us had the whole story, and I suspect that most of us had long forgotten or misplaced the memories we had – but somehow, when we started to reminisce and ‘ditt’ together, our collective memory became greater than the sum of the parts. Our memory had been socially reconstructed from distributed, social storage. It wasn’t just what we could remember ourselves, it was what we sparked back from our deeper memories.

It got me wondering how much opportunity we give to this kind of reflection and retrieval when we consider our organisational knowledge.

- Is it built largely from individual expert interviews, webinars and artefacts?

- Are we missing out on what we could re-construct together?

- Can we do more with processes and tools to access the kind of collective organisational memory and learning which is more insightful than the sum of our individual memories?

And what about the reverse process - when we disband teams, or retire experts - what is the impact on the availability of knowledge?

It's easy to assume that when a team dissolves, each of the members take the knowledge, lessons and stories with them. Completely. Within this assumption, every team member is a repository and can be managed and reallocated as a lossless, portable knowledge transfer approach, plugged into the next project just like a lego brick.

My experience is that many of the stories and insights don't reside wholly with an individual - they only surface when two former team members (or school mates) come together and spark each other's memories to release the value. Without the other half, the knowledge value of that shared story is volatile, and at risk of dispersing into the ether.

In this world there is a real loss of knowledge when a team is disbanded and reallocated - it's not all carried by the individuals, recoupable from a set of separate interviews. The sum of the separated parts is now less than the sum of the parts when they were together.

If you can remember your school Chemistry, you might say that shared memory is a covalent bond, not an ionic one!

Perhaps the Beatles were right all along, that we really do get by with a little help from our friends.

What's in a name

Or perhaps, more accurately – ‘What’s out of a name?’?

I’ve been working with the UK Government’s Dept for International Development (DfID – aka UK Aid) over the last two years, and was recently struck by the way they name their Learning & Development function. They call it ‘Capability and Change’.

I really like that because it speaks to the outputs and outcomes of the work of the team, rather than the inputs they provide. And outputs and outcomes are what matters.

Agri-chemicals company Syngenta are also deliberate in this focus on what matters, but in the way they describe meetings and events. They have a great little structure which they call a PO3. (The one-time Chemist in me took a little while to establish that they weren’t talking about Phosphite ions.)

PO3 stands for ‘Purpose, Objectives, Outputs & Outcomes”. If you are invited to a meeting in Syngenta, you’re likely to be sent a ‘PO3’ along with the agenda or itinerary – so before you even arrive, you’re clear about the strategic purpose and specific objectives for the activity; you know what should be produced in terms of decisions and documents, and you have a good idea of the ‘undocumentable’ benefits of the meeting, and how it supports change.

I think it’s a great little tool. It’s one of the privileges of consulting that you get to pick up, use and transfer (with accreditation) nuggets like this from one client to another. The PO3 is definitely one of those.

So getting back to names which are focused on outputs and outcomes then. If Learning and Development becomes ‘Capability and Change’, then what does Knowledge Management become?

Ultimately, of course, the outcome should be business value – but that’s true for every management philosophy and improvement methodology isn’t’ it? So if we work back from that ultimate goal, what are the distinctive that knowledge management delivers?

For me, I’d summarise it as an I3. (Nothing to do with tri-iodide ions or hybrid BMWs)

Improvement, Insight and Innovation.

Those should smell sweet enough to any organisation.

Is KM a quick fix or a slow burner?

BBQs, Brais, whatever you want to call them, they’re one of the reasons that Summer evenings are the long, relaxing family times that they should be.

After years of using, abusing and replacing BBQs of various types and sizes, I succumbed to the marketing of the Big Green Egg Company and bought one. I admit, it was an indulgence – but I love it!

For the uninitiated, it’s a ceramic, charcoal-fuelled BBQ/grill/smoker which (according to the advert) can cook pretty much anything – but does particularly well at slow-roast hickory-infused joints of pork, lamb, beef – gently smoking away for up to 8 hours at a time, until is just falls off the bone. Mmmmm. Now I’m starting to drool.

I had a call today with a long-standing client in a UK’s government department. Over the last 4 years, I’ve been delivering a half-day leadership programme for their middle and senior managers, entitled “knowledge sharing strategies”. During that time, nearly 400 staff have participated in a range of activities: inventing knowledge transfer approaches for the Olympic Games, flying with the Red Arrows and hearing from heart surgeons, reflecting on quotations from Einstein to Toffler, Prusak and Snowden, diagnosing the seven deadly knowledge-sharing syndromes and learning from leaders.

This client was excited to report that there were clear signs that the training was bearing fruit: after action reviews are becoming more widespread, project reviews have become more meaningful, people are experimenting with randomised coffee trials to connect across boundaries, subject experts are consolidating knowledge into ‘knowledge assets’ which connect back to their SharePoint repository, people actively consider learning before doing, knowledge loss is being addressed as a real risk, and leaders are more aware of how their own behaviours and questions can shape the environment for knowledge-sharing. There’s still a long way to go to join up these puddles of good practice in to a river of improved performance, but it’s really good to see evidence of real change. The programme continues…

So what’s the connection between my Big Green Egg and that client conversation?

It’s all about patience and time.

If my 20 years working in the field of knowledge management have taught me anything, it’s that whilst there may well be quick wins, there are no quick fixes.

Some people perceive KM the business improvement equivalent of a beef burger – pre-processed content, a quick grill, flip it over, and it’s ready for consumption.

Change the technology. Send out a management missive. Start up a discussion or implement microblogging and call it a community, then look for the benefits in a few months.

My experience is that a sustainable implementation of knowledge management is far more like a slow-roasted joint of meat – well-chosen, marinated and prepared. We’re talking about hours rather than minutes, depending on the tenderness and cut of the meat in question – but the smokey aroma reminds you that it’s worth the wait.

In just the same way, when we consider strategic KM, we’re talking in terms of years rather than months. For this client, it’s taken 3-4 years to see great examples emerging – some organisations are more ‘tender’ and change comes more rapidly – but generally KM is a slow burner. That’s not to say we don’t need to identify quick wins, or sparks of inspiration as we go. Most change programmes need a steady trickle of these to keep sponsors happy and keep the faith and morale high in any implementation team – however, let’s not settle just for the quick wins and lose sight of what’s really possible.

Just as we wouldn’t invest in a Big Green Egg to just to grill burgers – let’s ensure that our impatience doesn’t deny us the long-term, lasting benefits of a knowledge-enabled organisation. That might mean that we have to re-educate the business palate of a few key people – but in the end, it’s well worth it…

Now isn’t that much more appealing than a burger?

Finishing the unfinishable. Where lessons should lead.

I had the pleasure of working in Edinburgh today, and flew in over the Forth Bridge (the rail bridge). It’s an iconic engineering landmark and a symbol of Scotland, which was recognised earlier this month by UNESCO as a world heritage site.

What this bridge is most famous for though, is that the task of ‘painting the Forth Bridge’ has become a metaphor for never-ending, unfinishable jobs. With 240,000 square metres of steel to cover with 230,000 litres of paint – no sooner have the painting team finished the job, that the weathering processes mean that they have to start again.

Until recently that is.

Four years ago, new innovative epoxy paint with glass flakes was used on the bridge – the same paint that is used by the offshore oil industry. The new coating is predicted to last 25 years, ending the 120-year tradition of continuous painting. (Well, let’s face it, they needed a rest!)

This is a helpful metaphor for lesson learning in organisations.

It’s not unusual for the same lessons to learned over and over again by different teams in the same organisation.

It’s not uncommon for the same lessons to be captured over and over again in the same system.

It’s not uncommon for other teams to be well aware of the lessons which their peers learned before them.

Sometimes they even modify their plans accordingly – but even that shouldn’t be seen as the end-game.

Effective lesson-learning isn’t predicated on the endless handover of the same knowledge and learning baton from team-to-team. That’s just like the ‘painting the Forth Bridge’ cliché. Learning is transferred but nothing fundamentally changes as a consequence.

In 2011, something fundamentally changed with the Forth Bridge. Insights from the use of paint in another industry was suggested, tests were conducted, a business case was formed, a decision was made, a project was funded a specialist painting contractor received a lucrative contract (and the incumbent paint supplier lost an established customer), the old paint was blasted off and the new paintwork was completed after a ten-year effort. The unfinishable was finished.

Learning, Innovation, Adaptation, Change, Improvement, Value Creation.

The future of Knowledge Management – Births, Deaths or Marriages?

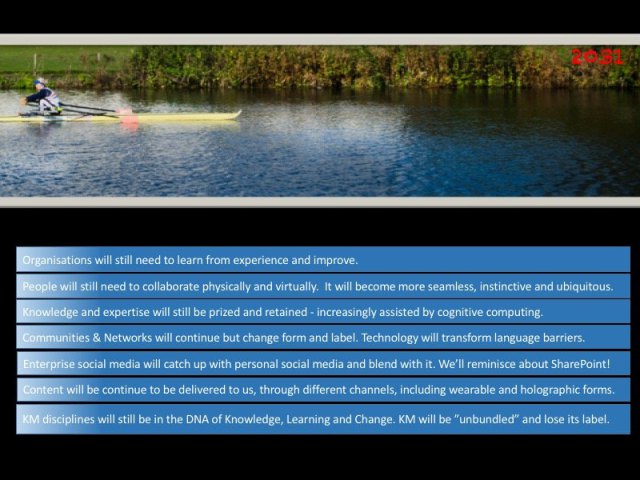

A few months ago I was asked to present at Henley Business School’s annual conference on the past and future of knowledge management, looking backwards and forwards 15 years.

Without sharing the whole presentation, here is a summary of my thoughts.

My own family has changed dramatically in that time – as Hannah, my 15 year-old will testify! In several respects, KM hasn’tchanged a great deal over the past 15 years. Many of the practices which were pioneering approaches in 2001 are still surprisingly effective and still surprisingly novel for some in 2016.

Not all practice are equal though. Different KM practices evolve and develop at different paces. For example: communities of practice and lessons learned go through gentle spirals and eddies of improvement and iteration whilst other developments seem to go past in the fast lane…

We have also seen significant shifts in KM due to changes in other related disciplines. The rise of enterprise social networks over the past 10 years has added much momentum to KM – probably changing KM’s mix and perception from then on.

At a high level, we have seen a shift from a focus on Knowledge capture and Information management – ‘just in case’ KM, which generated a response to information overload in the form of distillation and curation and the formation and management of knowledge assets – ‘just enough’. Timeliness – just in time’ knowledge is also a critical issue. As Dave Snowden once said: “we don’t know what we know until we need it”. And now ‘just for me’ knowledge comes with the growth of personalization and tailored knowledge flows over the last 5 years. 5 years ago, when we searched for the same word on google, we got the same result. That’s no longer the case.

Looking forward, I asked the SIKM community, one of the longest–standing KM leaders communities – for their thoughts on the key developments over the next 15 years. Technology will continue to disrupt (positively) the KM marketplace, but that doesn’t mean that human KM is going away – but we’ll continue to get better at it, especially as the nature of he employment contract, the psychological contract and the very nature of organizations shifts. IP will continue to evolve to keep the lawyers busy (the ones which haven’t been replaced by robots), as Open Data and the sharing economy combine with the changes to organizations to create what the Chinese might describe as “interesting times”. At an individual level, we’ll see more of a shift to personal social broadcasting. Periscope is just the tip of a bigger iceberg. Add personal drones, virtual reality and wearable technology to the mix and we’ll all be streaming and broadcasting in multiple dimensions. Google search will just have to keep pace.

What does all this mean for KM? The community had different views. They agreed that KM will be devolved further into the workforce, which could create a resurgence for expertise to help with that shift.

As part of its maturing, KM as an ever-growing umbrella may find that the unifying material has stretched too thinly to remain meaningful. How broad can a broad church become, before it loses the faithful?

Back to our river of ‘justs’… going on from ‘just for me’, I think we’ll see that increase in social broadcasting ‘just from me’ with our employees (whatever “employees” means then) – thousands of potential channels to tune into in real time. In 2001, our only employee “footprints” were emails! Think how much that will be enriched. And by the way, will any of us even use email in 2031?

Cognitive computing will better anticipate our knowledge needs based on current context, history, geography, proximity to others – and suggest answers to the questions we hadn’t even though to ask ourselves. ‘Just thought you should know’

Ultimately, some of those decisions will be made for us – ‘just decided for you’ – and we will have to decide what we, and our children do to thrive in that world.

My predictions for the future of KM?

Some things are ‘evergreen’. People will always need to talk, learn, reflect,

network, collaborate and interact.

Expertise will continue be prized, but the bar will be raised on machine learning. Employment boundaries will change and become more permeable; communities and networks will become more flexible. HR will finally embrace the strategic, people-oriented elements of KM, and we’ll see it at the heart of OD capability, rather than on the periphery.

Technology will change significantly, offering huge opportunities to a smaller number of people who understand how to integrate behaviour, understanding and technology.

So for KM? I don’t think we’ll be using the label in 2031 – but well recognise today’s KM DNA in a series of sub-disciplines which it has become unbundled into. Knowledge, Learning and Change will still be fundamental to success.

A couple of years ago, a respected thought leader in KM blogged that KM wasn’t quite dead, but was in its death throes. I think he confused death throes for labour pains. We’ll see KM as the mother and father of many thriving child disciplines.

However, just like my daughters Martha and Hannah – these child disciplines may one day chose to marry and take on a new surname – but they will always have my DNA.

A time to write, a time to talk...

Two things have got me reflecting on how we decide when to write and when to talk.

Yesterday I had the privilege of spending the day with a regiment in the British Army, helping them to apply knowledge management and organisational learning. Over dinner in the mess, the officer next to me was telling me that he had overseen a successful social event for the regiment during the previous year, and that he was passing on the baton to another officer to do the same this year. He was personally frustrated that he hadn’t yet considered what he had learned, or written any procedures for his colleague – and was unlikely to have time to do so. “Why don’t you just talk together over a beer?” I asked?

I won’t forget the look of relief on his face!

Such is the cultural emphasis on formal codification in his military experience that he hadn’t really considered a more informal method of sharing his knowledge. I got them together after the dinner over that beer and happily told them that ‘my work here is done.’

Secondly, this entertaining TED talk by Elizabeth Stockoe (Professor of Social Interaction at Loughborough University) illustrates so well the conversational richness which is accessible to an expert like Elizabeth, and the way in which it can be encoded and analysed – and how much I would have missed! It made me appreciate afresh the knowledge we lose in codification – so much of the message never makes it into the written record. Bullet points really do kill knowledge.

So these two inputs have got me reflecting on this typical exchange:

“Can we have a chat about what you think about this project?”

“Let me email you some thoughts as soon as I’m back online…”

We make this kind of decision every day, often subconsciously. Shall I send a message/email; shall I pick up the phone; should I drop by and talk face to face, or over a coffee? Whenever we do this, we’re making a decision about the relative value ofcodification versus conversation. In a sense, we execute our personal version of a KM strategy on a micro-scale.

Each approach has its own efficiencies and trade-offs:

Codification creates an record of the message, and provides an opportunity to multiply its reach for free, and releases us from doing anything at a specific moment in time. Write (and edit) it once, when you have time – and then share your message with as many people as you like.

However – as Dave Snowden says – “we will always say more than we can write down” – so when I decide to ’email you some thoughts’, I am making the judgement that:

- the tonality and visual cues which would present in a spoken conversation can be left out with minimal damage to the message;

- that I can capture enough of the necessary detail unambiguously in writing in time for it to be useful to you,

- that I can anticipate the questions which you might have have asked,

- and any that new direction which a conversation might have taken probably wouldn’t have been of great value..

These four points would be addressed through conversation – but that requires us to agree a time to connect – so the exchange is no longer on my terms.

Other factors and preferences also come in to play: Am I energised by social interaction, do I enjoy this person’s company, is this a relationship which I should invest in?

I think we balance this equation subconsciously – so doing some of my thinking out loud here has helped me to examine the relative weighting I give to each factor.

All of which has led me to a new year resolution:

write less and converse more

Lessons Lost

Image accredited with thanks to Paul Sapiano

Following on from my last post comparing operational effectiveness with knowledge effectiveness, I’m reminded of the “Choke Model” from my BP days. The choke model was a way of modelling production losses at every stage in the process, for example during the refining of crude oil to produce the raw materials and refined products which customers want to buy. Starting with 100%, every step in the process was analysed, and the biggest “chokes” were identified and targeted for improvement. There is a belief in BP that the total of all of these small percentage production losses across all of its refineries was the equivalent to having a brand new refinery lying dormant! Now when you focus it like that, it’s one big financial prize to get after.

I think there’s a similar perspective that we could take looking at the way in which knowledge is lost during our efforts to “refine it” and transfer it to customers. Sometimes we are so upbeat about “lessons learned” and “learning before, during and after”, that we start believing that we’ve got organizational learning cracked. I don’t believe that! Let’s take a walk through an organizational learning cycle and see where some of the “chokes” in our knowledge management processes might be.

Imagine that you’re working with a team who have just had an outstanding success, completing a short project. There’s a big “bucket of knowledge” there, but from the moment the project has completed, that bucket is starting to leak lessons. (On a longer project, the leakage will start before the project has ended, but let’s keep it simple for now and imagine that memories are still fresh).

From this moment, your lessons start to leak. The team will be disbanded, team members join other projects, and people start re-writing the history of their own involvement (particularly as they approach performance appraisal time!).

Leak!

So we have a project review to capture the lessons. Good – but not a “watertight” process for learning everything that might be needed.

- Are the right people in the room? Team? Customers? Sponsor? Suppliers? Partners?

- Are you asking the right questions? Enough questions? The questions which others would have asked?

- Are people responding thoughtfully? Honestly? Are people holding back? Is there politics or power at play which is influencing the way people respond? Is the facilitator doing their job well? Are they pressing for detail, for recommendations, for actions?

Leak!

And then we try to write-up this rich set of conversations into a lessons learned report. However hard we try, we are going to lose emotion, detail, connections, nuances, the nature of the interactions and relationships – and all too often we lose a lot more in our haste to summarise. Polanyi and Snowden had something to say about that.

Leak!

And what happens to that report? Is it lost in the bowels of SharePoint? Is it tagged and indexed to maximise discovery? Is it trapped on someone’s hard drive, or distributed ineffectively by email to “the people we thought would need it”?

Leak!

And of course, just because it’s stored, it doesn’t mean it’s shared! Sharing requires someone to receive it – which means that they have to want it. Are the potential users of this knowledge hungry? Curious? Eager to learn? Encouraged to learning rather than reinventing? Infected with “Not invented here”? Believe that their new project is completely different? Willing to root around in SharePoint to find those lessons? Willing to use the report as a prompt to speak with the previous team, and to invite them to a Peer Assist to share more of their learning?

Leak! Leak! Leak!

So you see, it’s a messy, leaky, lossy business, and I think we need to be honest about that. Honest with ourselves as KM professionals, and honest with our colleagues and customers.

That doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t work hard to address the leaks and losses - quite the reverse. We should be anticipating and responding to each one. Whether that means having a “knowledge plan” throughout the lifetime of a project, engaging leaders to set the right expectations, providing support/training/coaching/facilitation/tools etc. There’s a lot we can do to help organisations get so much better at this. They might not save the equivalent of a Refinery’s worth of value – but they might reduce their dependence on external consultants.

I think it starts with the question – “how valuable do we believe this knowledge is?”. If you look at the picture at the top of this blog and imagine it’s happening on a beach somewhere, then it’s just part of the fun in an environment of abundance. You can fill the bucket up again and again...

If the picture was taken in a drought-stricken part of the world – an environment of scarcity – well that’s a different story.