This Google sponsored link appeared for me today on a search for knowledge management...

It made me smile to myself, because of course, one of the top ten mistakes in knowledge management is...

...to talk about "best practices"!

Your Custom Text Here

This Google sponsored link appeared for me today on a search for knowledge management...

It made me smile to myself, because of course, one of the top ten mistakes in knowledge management is...

...to talk about "best practices"!

Having been working in this field for over 15 years now, I've finally got around to recording a short video which describes what's "under the umbrella" of knowledge management! David Gurteen has been asking people this question for years and recording their responses, but never seems to have his camera when we meet.... (at least, that's what he tells me!)It's harder than I thought - KM is such a "broad church" now, so I've done my best to be reasonably succinct. There are still bits which I missed, like the contribution it makes to ideas generation and innovation - but perhaps I'll leave that for another video, another time!

Here's the transcript:

Knowledge Management is a set of tools, techniques, methods, ways of working, even behaviours - that are all designed to help an organisation to be more effective. Simple as that.

So how then does knowledge management differ from other toolkits or management movements like SixSigma or Lean?

To me the difference is that Knowledge Management focuses on the know-how and the know who – how do you put that to work more effectively in an organisation. How do you share the key points, rules of thumb? How do you ensure that the right contacts are made such that people have the conversations they need to have at the beginning of a project, before everyone gets into action? So for that reason Knowledge management is quite a broad church of techniques and approaches (for me, that’s what makes it so interesting!).

So you could find yourself looking at tools which help you to identify and support the networks or communities ofpractice in an organisation, ways of mapping how people are connected, ways of improvingthose connections - looking at who talks to whom, who trusts whom, and how you can optimise that.

You could equally look at how good an organisation is at learning – learning before activities, learning after activities. How do you ensure that the lessons you capture after a project are meaningful and full of recommendations and useful actions points for somebody.

It could be about how you encourage a team to learn continuously, rather than waiting until the end of major project before they take the time to pause and reflect.

It could equally well be about how we capture knowledge such that the value can be multiplied. How do you take a nugget or insight and capture it in such a way that people are intrigued, interested, want to read more and want to get in touch with the person who wrote it. How do you package that up in a way which doesn’t destroy all of the emotion, the context, but seems to carry it with it . Much more use of multimedia, much more use of connections to some of the social media tools, so that you’re only ever one click away from a conversation. Finally it has a lot to do with the way we behave, the way in which we work, the culture which we establish and support or nurture, or come against as leaders in organisations. How do you come against a “Not-invented-here” culture? How do you support and make it safe for people to share their experiences and learn from those, to share their failures as well as successes?

Knowledge management encompasses all of these things, behaviours, technologies, processes. learning, networks - and for me, that’s what makes it such an exciting discipline.

Just finished my column for the next edition ofInside Knowledge, exploring someof the barriers to knowledge-sharing in organisations. Whyis it sometimes so difficult to motivate people to share good practices - or to encourage people to look to others for potential solutions?I've looked into four syndromes which impact either the "supply side" or the "demand side" in any knowledge marketplace: Tall Poppy Syndrome, Shrinking Violet Syndrome, Not Invented Here Syndrome and finally TomTom Syndrome (aka "Real men don't ask directions"!)

Here's the video to go with the article...

A sneak preview of my up-coming column in the next edition of Inside Knowledge... During my childhood, I wiled away many an hour with school friends and a pack of Top Trumps cards. For the initiated amongst you, Top Trumps consists of a set of cards based around a particular topic. (In my day, it was ships, racing cars, Olympic medallists or dinosaurs. Today, it’s more likely to be X-Factor contestants or Harry Potter characters). Each card contained statistics about the car or dinosaur in question, which enabled you to compare scores with your friends and - if you chose the right category - to win their favourites until you possessed all of the cards. One of the side effects of overdosing on Top Trumps would be the ability to recall facts and figures about any card. To my slight embarrassment, I can tell you without pausing that the 0-60mph acceleration of a 1978 Lamborghini Countach is 5.6 seconds. Too bad my short-term memory is unable to recall where my own car keys are right now!

Last month I had the opportunity to work with a network of business improvement professionals (the I&I Network) who wanted to understand where knowledge management tools and techniques could complement their world of LEAN, Six Sigma and Kaizen. Sensing an audience of potential Top Trumps sympathizers, I made up packs of “KM Trumps” for them to play with in pairs for ten minutes. For my categories, I chose: Cost, Return on investment, Learning curve, Geek Factor and Engagement Effect. I had difficulty stopping their game to continue the workshop with them! I found that even in those few minutes, everyone picked up on the breadth and variety of tools which we place under the KM banner. When all 36 cards were laid out, with their categories visible it was easy for my group of improvement specialists to make an informed selection about the tools and techniques which might best fit their own organisations. They could tailor their own custom toolkit with just the right amount of “Geek Factor” and not too much learning curve.

One of my bugbears in KM circles is the way in which the labels KM 1.0, KM 2.0 and even KM 3.0 are used - as though knowledge management is only allowed to exist in a number of quantum states; or it’s a branch of scientology... Don’t get me wrong, I’m a big fan and big user of social media, and I think it has brought energy, connectivity, serendipity and a real-time edge to the field of knowledge management. What it hasn’t done is to supersede the fundamentals of KM – the value of conversation, the importance of learning and reflection, the power of communities of practice, the need to both summarise and provide stories to preserve context. Superceded? No. Provided a welcome shot of adrenaline? Absolutely.

I believe that as KM professionals, we have a duty to remain aware of, and open to, the new tools and techniques which come our way. Where we add value is in explaining how and when an approach or combination of approaches can have the biggest impact. That might mean that this year, your organisation is KM 1.6, and next year it’s KM 2.17. It’s our job to find out what number our organisations need.

Sometimes we might be surprised that a simple, established KM tool has the biggest impact, just like I was surprised when my school friend trumped my prized Lamborghini card with his Isetta Bubble Car. All because he was smart enough to choose fuel consumption as his category, rather than acceleration!

Just enjoyed an excellent 3 days at the 10th anniversary Henley KM Forum. Against my better judgement, I provided (together with Martin Fisher), a little musical interlude as part of our project report on "knowledge-enabled project management", where we were exploring the perceptions that project managers have regarding knowledge management, and vice versa. So here is it, just in case you ever need it - Music courtesy of Frank Sinatra, words courtesy of yours truly... KM (Frank) in black, PM (Nancy) in red!

Enjoy!

Somethin 'Stupid (will KM and PM ever fall in love?)

I know I’ll stand in line

Until you think you have the time

To have a meeting with me.

And when I tell you all about

The way to give your project clout

You’re pleading with me.

On time and cost and quality, your eyes grow large as you can see

why I’ve been sent.

But then I go and spoil it all by saying something stupid

Knowledge management!

I can see it in your eyes

That you despise the same old lines

You think it’s just a fad.

I’ve got my targets and my plan,

I manage risks, you understand?

D'you really think I’m mad?

I manage all my stakeholders

and fill up all my sharepoint folders.

That’s what I do.

I’m learning all the lessons though

I don’t know what’s the best one,

Or if it’s really true.

My project is unique,

No-one would seek to hear me speak, my learning to present.

And now you’ve gone and spoilt it all by saying something stupid

“Knowledge management...”

If you were in my shoes

You mustn’t lose, what could you choose

To keep the board content?

I guess we’d find a way to save the day by just applying...

Knowledge Management

Through Project Management

<together> Good Management... (to fade...)

With the schools snowbound and closed for a few extra days last month, I persuaded my daughters to help me make an igloo. It’s something I’ve always wanted to do. It took a lot longer than I thought and the pretence that this was “Dad helping them” began to slip after a while as and my co-labourers needed a hot chocolate break or two along the way. I improvised with Tupperware boxes to make my bricks, learned as I went, and bullied/bribed my girls to hold up the walls when we got to the tricky bits. Getting the final block in the roof was an act of sheer desperation and good fortune. We made it! Not quite the classical dome shape, I’ll admit, but it lasted the night before a surprise skylight window appeared the following morning, quickly followed by total collapse. You would think that after 41 years of waiting for that perfect snow, I would have known exactly how to make an igloo; but I didn’t.There is no shortage of material, videos and step-by-step instructions on the web . A Google search on “how to build an igloo” yields 673,000 results, including some excellent step-by-step videos on YouTube. If I’d bothered to look at even the first two of these, then I would have known that the whole thing is built as a self-supporting spiral. After my first layer of snow bricks, I should have cut a shallow incline up the wall to create the beginning of my spiral; but I didn’t.

No, Google and YouTube didn’t let me down. The fact is, I just wanted to get out there with my brick-making and build.

It took a lot longer than I thought and the pretence that this was “Dad helping them” began to slip after a while as and my co-labourers needed a hot chocolate break or two along the way. I improvised with Tupperware boxes to make my bricks, learned as I went, and bullied/bribed my girls to hold up the walls when we got to the tricky bits. Getting the final block in the roof was an act of sheer desperation and good fortune. We made it! Not quite the classical dome shape, I’ll admit, but it lasted the night before a surprise skylight window appeared the following morning, quickly followed by total collapse. You would think that after 41 years of waiting for that perfect snow, I would have known exactly how to make an igloo; but I didn’t.There is no shortage of material, videos and step-by-step instructions on the web . A Google search on “how to build an igloo” yields 673,000 results, including some excellent step-by-step videos on YouTube. If I’d bothered to look at even the first two of these, then I would have known that the whole thing is built as a self-supporting spiral. After my first layer of snow bricks, I should have cut a shallow incline up the wall to create the beginning of my spiral; but I didn’t.

No, Google and YouTube didn’t let me down. The fact is, I just wanted to get out there with my brick-making and build.

All traces of the igloo have now melted away, but I’m left reflecting on the way I approached the challenge. How often in an organizational situation do we get carried away with misplaced self-belief, a little (but not enough) knowledge, a little too much ego and an eager desire to just roll up our sleeves and get on with it? How often do we deliver something that looks roughly right, but like my igloo, doesn’t withstand the test of time?

All traces of the igloo have now melted away, but I’m left reflecting on the way I approached the challenge. How often in an organizational situation do we get carried away with misplaced self-belief, a little (but not enough) knowledge, a little too much ego and an eager desire to just roll up our sleeves and get on with it? How often do we deliver something that looks roughly right, but like my igloo, doesn’t withstand the test of time?

As knowledge professionals, it’s easy to sink time and money into making content more easily accessible, navigable, and searchable. We can construct elegant wikis, enliven our intranets with RSS and real-time twitter feeds, but none of this will guarantee a better outcome when people have their “igloo moments”. Sometimes, it’s not because people lack access to the knowledge or the time to find it. Rather it’s because they just want to get out there and try it their own way – because it’s something they’ve always wanted to.

So what might have caused me to build my igloo better?

Perhaps a friend out there with me in the garden that day, saying – “Hey, I’ve tried this before. If you want it to last, then need to build it this way...” A challenge for better performance from someone I trusted, and the benefit of their first-hand experience exactly at the moment I needed it. Now that’s a pretty good vision for a knowledgeable, learning organization.

Finally, just to prove that my jokes are no better than my igloo-building skills...

One Eskimo enviously asks another Eskimo: “Which book did you read to find out how to build such a perfect igloo?” The other Eskimo replies:

Urinals. Do you spend much time looking at them?

Urinals. Do you spend much time looking at them?This is just a guess, but for half of you, I’m assuming that the answer is “no”. The other half of you are wondering where I’m going with this line of enquiry.

If you have had the pleasure of using the urinals at Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam, you will have noticed that each one is embellished with a lifelike image of a fly, under the glaze – just near the drain. Initially I dismissed this as merely an example of quirky humour from a Dutch sanitary-ware manufacturer, but I was too hasty. Apparently, since incorporating the fly into their urinals, airports and other public places have noticed a decrease in the amount of cleaning required. Some of these have improved to the extent that they have saved money by reducing the number of cleaning shifts. If you haven’t figured out the link between the fly and the cost reduction, ask any small boy!

All of this got me thinking about how on-target we are in the way we exchange knowledge, good practices, worst practices and stories. Despite our best efforts, do people sometimes miss the mark when it comes to knowledge exchange?

As knowledge professionals, we work hard to use processes and social technologies to bring people together collaboratively. On some precious occasions, we get to design and facilitate face-to-face knowledge-sharing events. Occasionally, we even get to work on leadership behaviours and organisational design.

In all of these worthy activities, we sometimes forget that knowledge management can also help groups of people to agree upon and describe their practices – and hence connect and share more efficiently because they have negotiated a common language.

Here’s an illustration. In KM circles, we have talked for years about the value of nurturing communities of practice, and rightly so. However, if we were to turn our “Community of Practice toolkits” out onto the table, the majority of our tools play into the notion of Community: role descriptions and training programmes for leaders and facilitators, templates for community charters, designs for launch events, no end of technology options for social collaboration and document management.

But what about the Practice bit? Do we have anything in our toolkits to offer groups of professionals who want to agree upon “what’s important” and describe “what good looks like”? Yes, we can provide wikis where people can discuss and build glossaries, definitions and reference material, but that’s a platform, rather than a process.

I’m advocating that as Knowledge Management professionals, we should be able to offer any group a simple process for describing their practices qualitatively, thereby enhancing their knowledge-sharing. That could involve the creation of a self-assessment tool (maturity model) – or perhaps a knowledge asset which helps others to navigate through a distillation of past learning, current good practice, examples and key contacts.

That’s more than installing a wiki, a Drupal community or a set of SharePoint libraries. It requires us to roll up our sleeves and engage with the subject experts and practitioners. It involves us in helping them to agree and describe their practice in an accessible way. By helping them to produce a common model of the practices which make up their functional area, they will be able to target their knowledge-sharing far more precisely, and hence get more value from KM tools and techniques.

Or to put it another way - if our knowledge workers have something more clearly defined to aim at, then we’ll have to spend less time clearing up after them.

At last! After over a year of blood sweat and tears, a small forest of paper, a well-used box.net collaboration space and far too many late night emails, Geoff Parcell and I have written another book together. To the alarm of my wife and children, not to mention my mortgage lender, this one is entitled "No More Consultants. We know more than we think."

So are we really saying that there is no need for consultants?

Jon Theuerkauf, MD at Credit Suisse answers that question perfectly for me in his endorsement on the back of the book:

"Look, of course we need outside input, if not we might as be staring at our belly-buttons. The point that is being made in No More Consultants is companies spend pennies in mining their own internal knowledge and expertise compared to the multi-millions spent on going outside first! How does that make any sense or cents?"

And that's exactly it. We really do know more than we think. But we don't think enough. Geoff and I wrote the book to guide organisations towards making smarter, more purposeful, more targeted use of consultants. After all, nobody ever got fired for hiring <<insert your favourite management consultancy here>>. That might be true - but a whole lot of your staff might have become disenfranchised. The same staff, who (after the glossy PowerPoint presentation has been delivered, and that large invoice has been submitted) will be expected to help implement the recommendations. Recommendations which perhaps they could have come up with themselves.

If only they'd been asked.

As Jon so neatly puts it. How does that make any sense or cents?

Hope you enjoy the video. And the book.

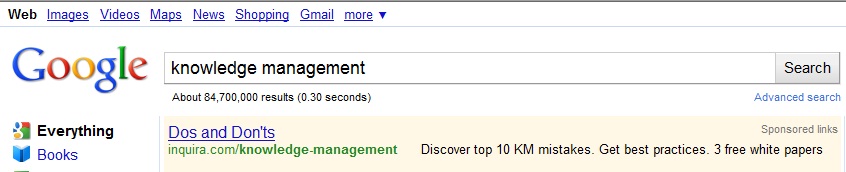

I had the opportunity to visit University College London Hospital (UCLH) last week (but not as a patient!). Two years ago I blogged about their visions to become University College Learning Hospital, and the efforts that they were making to introduce After Action Reviews into the culture of the Hospital. Two years later, they have developed their Learning Hospital – an environment where full simulations - administrative, board meetings, clinical situations - could be carried out with actors.

This very real experience is then the basis for staff to conduct after action reviews, to be videoed, review and discuss with their colleagues, together with the Learning Hospital expert staff. So far, 400 staff have become “AAR Conductors”, carrying out reviews in a variety of situations.

This very real experience is then the basis for staff to conduct after action reviews, to be videoed, review and discuss with their colleagues, together with the Learning Hospital expert staff. So far, 400 staff have become “AAR Conductors”, carrying out reviews in a variety of situations.

I was struck by the sheer quality of the Learning Hospital and also their innovative marketing approach. I liked the take-off of “being John Malkovich”, in which a selection of AAR Conductors had their fifteen minutes of fame.

It's a real credit to Steve Andrews and Professor Aidan Halligan - and I'm not doing them justice in such a short blog. I'll write a more considered piece with them and post it in the future...

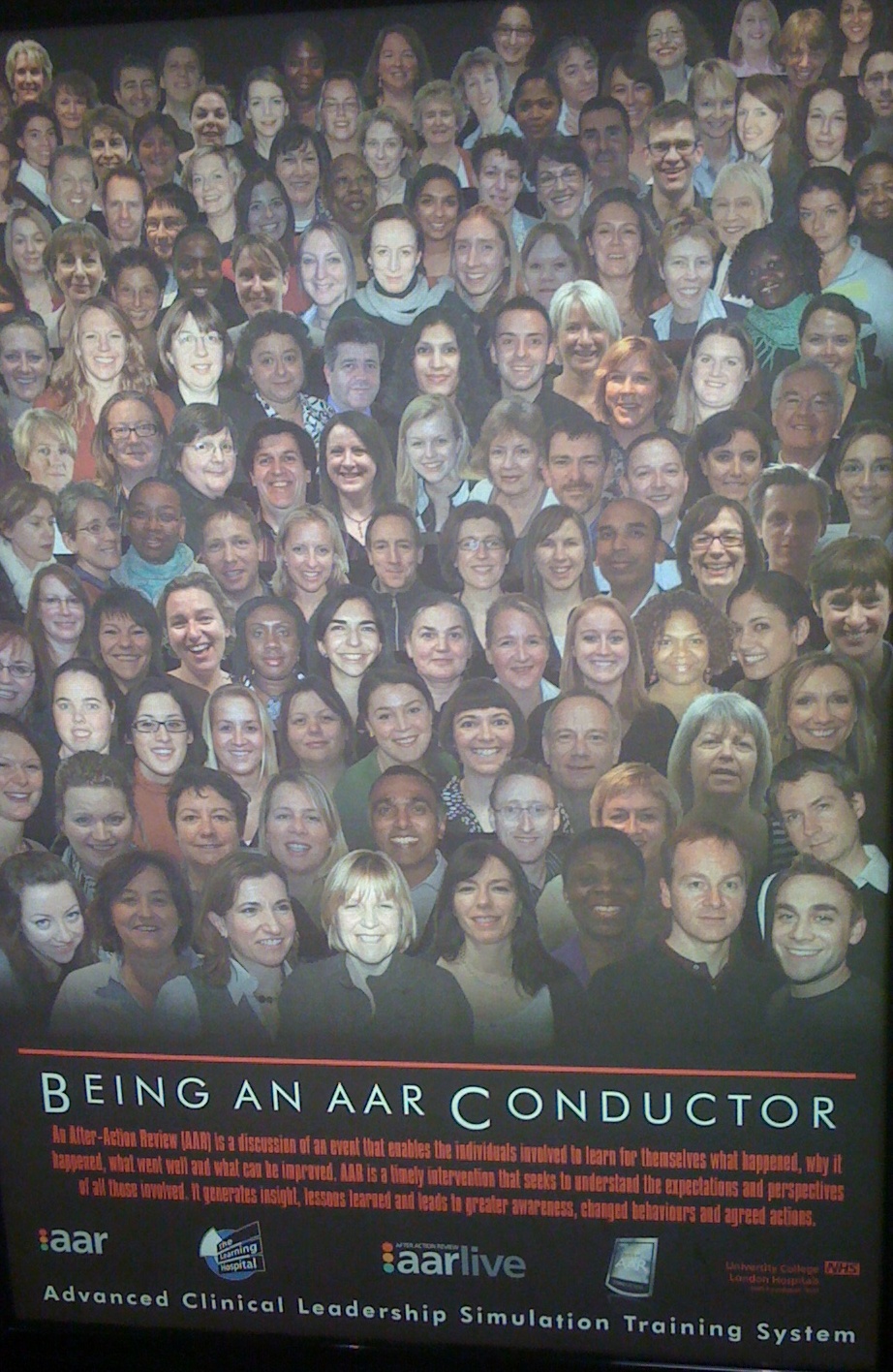

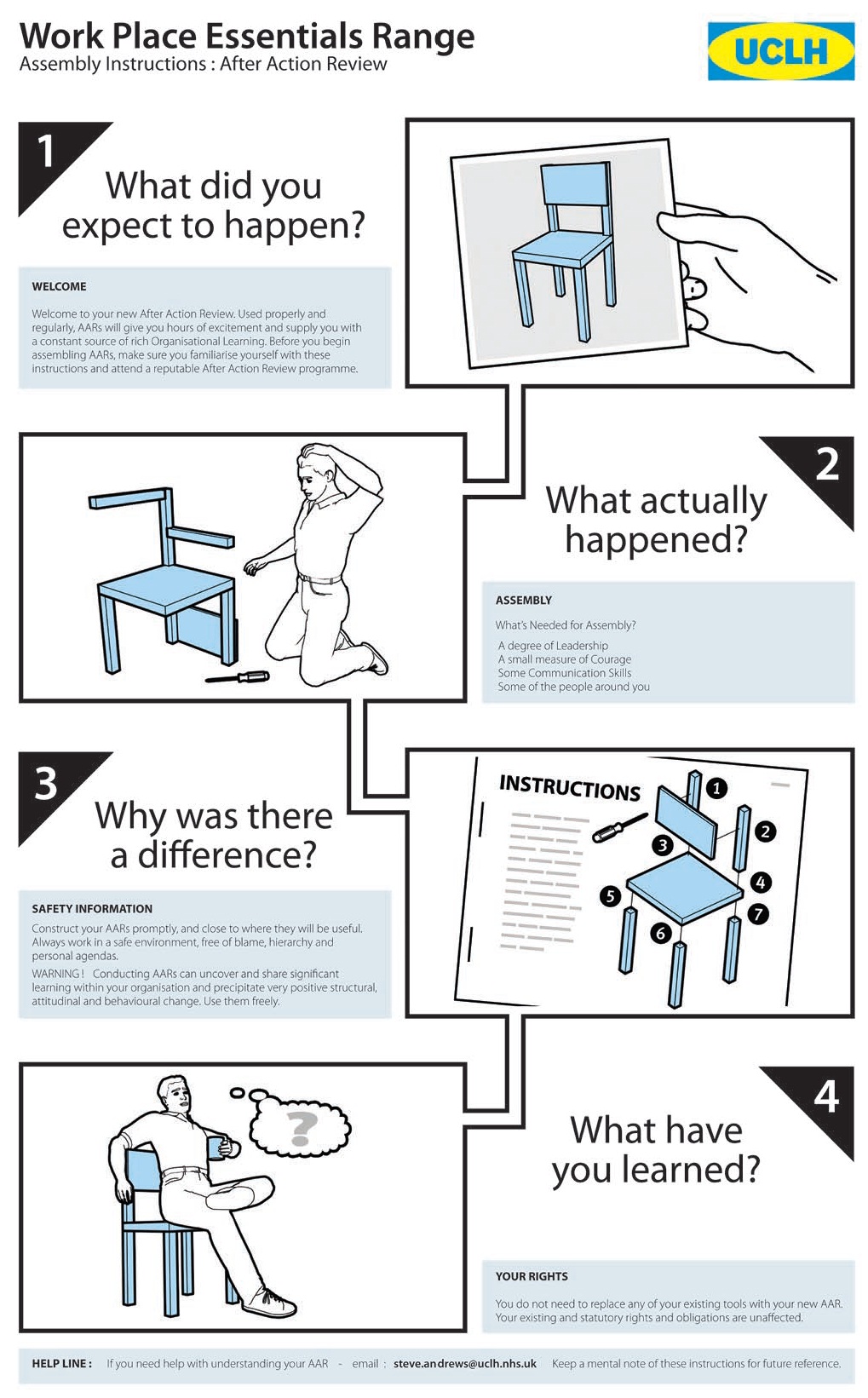

Of all the marketing posters though, I loved the IKEA After Action Review instructions the most - perhaps because I could identify with them so well!

Inspired, Steve! The US Army would be proud of you!

Came across this article on the BBC website today. Interesting to read the interpretation that power of "social learning" in the chimp community is so strong that the chimps stopped innovating and adapting, and complied with "what they had learned" - however inappropriate and suboptimal that approach was.

Now we can all smile at the chimps with their sticks and grapes - but I can see some parallels here with how culture develops in organisations, and what we learned once about something which works, left unchallenged becomes a barrier to future adaptation. Which in turn, is why I have such a struggle with the term "best practice".

Reminds me of the old apes, the banana and the water spray story.

Here's the BBC article:

Copycat chimps build their own tools after watching video demonstrations.

During a study, the animals were shown footage of a trained chimp combining two components to construct a tool that enabled it to reach a food reward.

When given the same two components, the chimps made their own tools and used them to drag over a tasty treat.

Reporting in the Royal Society journal Proceedings B, scientists say this demonstrates what a "potent effect" social learning has in the primates.

Elizabeth Price, from the University of St Andrews in Scotland, led the research.

"With video, we can control exactly how much information the animals see, so we can understand exactly how much information they need to work out how to do the task," she explained.

This type of behaviour is very rare in the wild

Elizabeth Price St Andrews University

Dr Price and her colleagues put the chimps into five groups during the test.

One of the groups was shown the whole demonstration - where a chimp was handed a rod and a tube that it slotted together. The demonstrator then used this longer composite tool to retrieve a grape from a platform outside its cage.

The other groups were shown progressively less information - with one group just shown the chimp eating its grape.

The researchers then recreated the set-up for the subjects.

They placed a grape on a platform against the outside of each chimp's cage, and handed the animals a rod and a plastic tube.

"Those chimps that saw the full demonstration learned better how to construct the necessary tool (to reach the food)," Dr Price told BBC News.

"The fact that they can learn how to build a better tool for a particular task is very exciting. This type of behaviour is very rare in the wild, and it's an essential part of human tool use."

Watch and learn

"A handful of the chimps that weren't shown the full demonstration learned how to make the tool on their own," said Dr Price.

Chimpanzees usually modify sticks by stripping them of their leaves

"What was interesting about this group was that, when we presented them with the grape at different distances from the cage, they made the appropriate tool to reach it."

Rather than faithfully copy the demonstration, these animals switched between using the unmodified tube or rod, and using the combined tool, depending on how far away the grape was.

"Those that had been shown the full demonstration, and had socially learned to make the longer tool, continued to make it even when the grape was so close that it was more awkward to use," said Dr Price.

"It could be that social learning is such a strong force for the chimps that they apply a blanket rule of 'go with what you've seen' (rather than work out what's most appropriate for the task)."

The team is now planning to carry out the same test in young children to find out how much they rely on social learning.

What the team still do not know why this type of tool-building is not seen more commonly in the wild.

"We've shown that they're clever enough, so there must be something else at play," said Dr Price.

"It may be that when chimpanzees reach an age at which they are... capable of performing these higher level techniques, they may be too old to have access to sufficiently tolerant demonstrators."