Have you heard the story of Billy Ray Harris? It's a heart-warming one.

Billy Ray is a homeless Kansas man who received an unexpected donation when passer-by Sarah Darling accidentally put her engagement ring into his collecting cup. Despite being offered $4000 for the ring by a jeweller, he kept the ring, and returned it to her when, panic-stricken, she came back the following day. Sarah gave him all the cash she had in her purse as a reward, and as they told their good-luck story to friends - who then told their friends - her finance decided to put up a website to collect donations for Billy Ray. So far, $151,000 have been donated as the story has gone viral around the world. Billy Ray plans to use the money to move to Houston to be near his family. You can see the whole story here.

On closer inspection, it turns out that this wasn't the first ring that Billy had returned to its owner. A few years previously, he found a Super Bowl ring belonging to a football player and walked to the his hotel to return it. The football player rewarded him financially, and gave him three nights at that luxury hotel. So the pattern was already established for Billy Ray, who also attributes it to his upbringing as the grandson of a reverend.

Whether you see this story as an illustration of grace, karma or good-old-fashioned human nature, it illustrates the principle of reciprocity.

Reciprocity is an important principle for knowledge management, and one which underpins the idea of Offers and Requests.

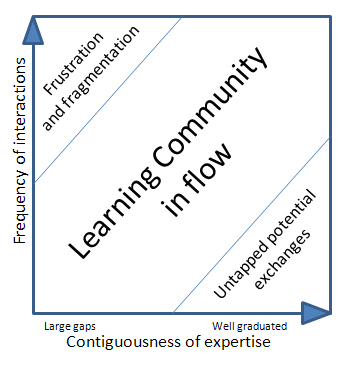

Offers and Requests was a simple approach, introduced to make it easier for Operations Engineers at BP to ask for help, and to share good practice with their peers. The idea was for each business unit to self-assess their level of operational excellence using a maturity model, and identify their relative strengths and weaknesses. In order to overcome barriers like "tall poppy syndrome", or a reluctance to ask for help ("real men don't ask directions"), a process was put in place whereby every business unit would be asked to offer three areas which they felt proud of, and three areas which they wanted help with. The resulting marketplace for matching offers and requests was successful because:

i) The principle of offering a strength at the same time as requesting help was non-threatening and reciprocal - it was implicitly fair.

ii) The fact that every business unit was making their offers and requests at the same time meant that it felt like a balanced and safe process.

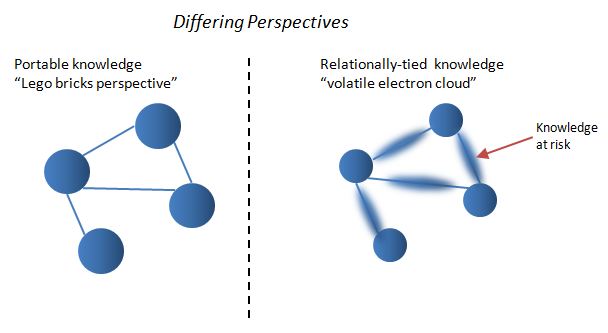

Like Billy Ray, one positive experience of giving and receiving led to another, and ultimately to a Operations community. A community website for offers and requests underpinned the process, enabling social connections and discussions.

This is played out in the Kansas story, where the addition of technology and social connections created disproportionate value - currently $151,000 of it.

In the words of Billy Ray, "What is the world coming to when a person returns something that doesn't belong to him and all this happens?"

Urinals. Do you spend much time looking at them?

Urinals. Do you spend much time looking at them?